Table of Contents

Crafting Adventures and Campaigns

An adventure is a series of challenges as part of a story that takes between one to three game sessions. A campaign on the other hand takes much longer to finish (if ever). It is a series of adventures that may be part of a larger narrative. With the longer timeframe, a campaign has more room for character development and plot devices like recurring villains.

To fit the limited timeframe of an adventure, the PCs should already be familiar with each other. If getting acquainted (and maybe keeping secrets) is an integral part of the story, it is important to give the PCs a motivation to go on a quest together. In any case, an adventure should start with a bang - an event that the characters can partake in and discuss. This could be a fight or a message being delivered to the PCs.

Goal

The goal of an adventure is always the same - that all participants have fun playing it. When you design an adventure and already know your players, you should talk to them and take their preferences into account. For some, roleplaying challenges are more important than combat, others may look for puzzles to solve or to defeat the most dangerous creatures or are invested into political intrigue. If it turns out that the group wants to take a different approach or follow another emerging story thread during the game, you may consider deviating from the adventure path. However, if the players just ignore a looming threat, it may happen anyway and catch them off guard.

Narrative Hook

The narrative hook or plot hook serves as bait for the players' interest. This is the description the players are given before the game and it includes vital information about the type of adventure. A plot hook should feature some mystery that sparks curiosity by raising questions and a subtle or explicit hint of reward. Another part of the hook may be a plea for help, an appeal to the characters' honor or a threat towards them. There might also be a moral dilemma involved. Will the heroes prevent great harm to their homeland or seek untold riches instead?

Examples

- The party has found a treasure map, but the hints on it are written in a strange language none of the characters has ever seen.

- An unnaturally large bird carries a caravan camel off to the peak of a nearby mountain. The caravan leader looks unsettlingly nervous as he asks the party to retrieve the camel's saddle bags.

- An estranged friend or mentor of a party member sends a message seeking a meeting with the party. However, when they arrive, they find the sender has been murdered in their apartment.

- The party has sparked the wrath of a deity and has been turned into different animals. Now they must find a way to change back.

- The party wakes up in a dark cave not knowing how they got there after getting drunk the night before. There is a massive boulder that had sealed the entrance but was recently moved. It seems like this was a prison for someone or something before the party arrived.

Backstory

For an adventure to be logically consistent, it must include a short backstory of events that lead to the current situation in adequate detail. This backstory is only fully known to the GM and may be reconstructed by the party through clues found during the game.

Plot Twist

An adventure may have a plot twist, an unexpected change of perspective or motivation behind the events so far. The plot twist is most effective when the party thinks it has already solved the mystery or fulfilled the mission. This may also be used to introduce a dilemma or as a cliffhanger for the next session.

The Adventuring Party

Most adventures are designed with a rough group size in mind. A fairly standard size is four to five players. The fewer players there are, the faster the group usually progresses through the story. The more players there are, the more mentally taxing it is for the GM and the longer it takes until all players have taken their turns.

Each adventure includes the starting levels of the PCs, their wealth as well as the amount of favors they start out with. When designing an adventure, the following table may be used for orientation.

| Type of Adventure | Character Level | Favor | Wealth |

|---|---|---|---|

| Low power | 10-20 | 0-1 | 100-300 |

| Medium power | 20-30 | 1-5 | 300-1000 |

| High power | 30-40 | 5-10 | 1000-5000 |

| Great power | 40-50 | 10-20 | 5000-20000 |

| Divine power | more than 50 | more than 20 | more than 20000 |

The characters' connections, background stories and roles within the group may be part of the adventure. To involve the players in such a way, the characters must be premade for the adventure or the GM has to discuss the characters' roles with the players beforehand.

This may involve getting extra information about the setting or guarding some kind of secret to add tension. Such a situation makes more sense in the frame of a full campaign, providing more possibilities for character development and roleplay interaction. Another way to encourage roleplay is to have some character's be related or in a professional dependency (e.g. one is the bodyguard of another).

Structure

When designing an adventure, try to avoid designing a linear sequence of events. The freedom of choice is a strong suit of tabletop RPGs. Preparing places, NPCs and items of relevance is important, but the order in which the party interacts with them and puts together pieces of the puzzle may change from one group of players to another. Naturally, a linear structure of events is unavoidable at times. However, sometimes the party will find a novel or unanticipated solution to a challenge. In this case, just roll with it and integrate it into the adventure.

Relevant Places

The layout of places relevant to the adventure is a useful tool for structuring it. You do not need to prepare a detailed map of every place, but you should describe it in appropriate detail to not hinder gameplay (a few sentences or bullet points are enough). To elaborate, there is no need to have the exact location of the buildings of town, but a list of the most important places or information about their existance should be available. When it comes to dungeons, maps of the rooms and their dimensions as well as the locations of traps may be necessary.

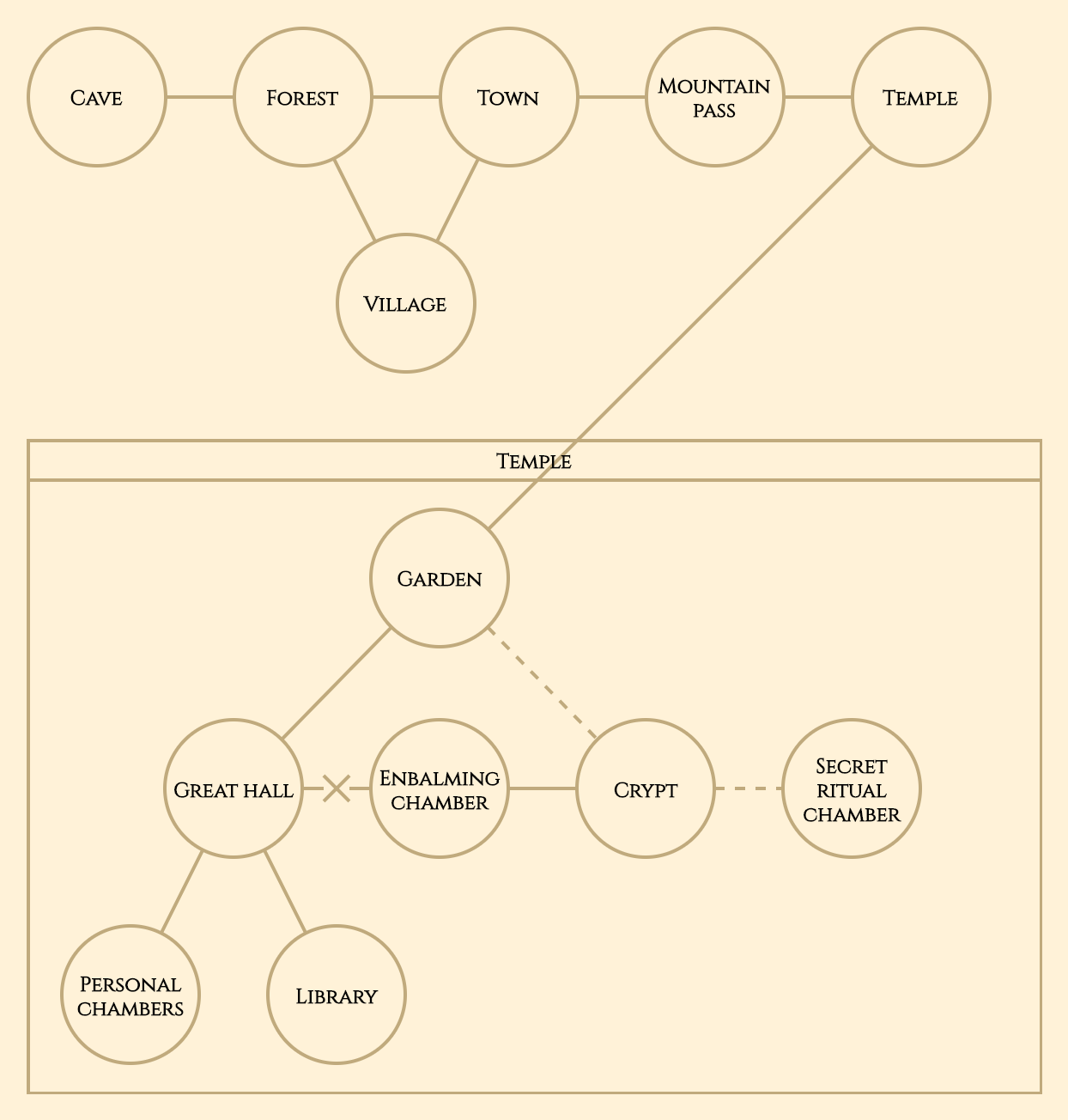

Places may be depicted as a graph of nodes and the connections between them. Each node may contain another more detailed graph. This allows the GM to have an overview of the adventure as well as its parts. Each node of a such a location graph may contain footnotes that lead to the descriptions of NPCs and items found at a certain place.

Example

The following adventure graph contains the relevant places of an example adventure where the temple has a subgraph depicting its components. Characters are able to travel from one place to another if they are connected with a line. A dotted line denotes a hidden access that has a challenge to be discovered. A crossed out line means that the connection is blocked by something such as a caved in ceiling or a barred door. You can also attach notes to each place about the NPCs, items etc. that can be found there.

Important NPCs

The NPCs that are directly involved in the adventure should be worked out and described in at least a few words. It is especially important what these NPCs are willing to share with the group and how to get them to do it. The NPCs may also have an aspect (a motivation or a weakness) that may be used by the party to defeat or gain the help of the NPC.

Special Items

Some adventures revolve around a special item (MacGuffin). It may involve retrieving, crafting, destroying, using or preventing the usage of the item in question or something similar. If the players are expected to use it or be the target of it, the item as well as its mechanics should be described in detail when preparing the adventure. This includes the item's location, who is currently carrying it and how it is currently used. If it is an item with mystical properties, the GM should know what kind of power resides in it.

Sequence of Events

Before starting the game, the GM should read through the adventure to make sure there are no plot holes or inconsistencies. Additionally, the designer of an adventure should reflect on the choices and possibilities in solving the challenges. Some clues may never be found by the party. Is there another way to solve a challenge in this case and what sacrifices are necessary in order to do so?